The Innovation Trail is a way to experience, learn about, and be inspired by four centuries of world-changing breakthroughs from Boston. Join one of our scheduled walking tours, or use this website to guide you on your own stroll through the history of science, medicine, entrepreneurship, and technology. We want the Trail to inspire you to create the next great innovation!

Changing perceptions.

When most people think of Boston, they think about the American Revolution—or higher education. They might walk the Freedom Trail starting in Downtown Boston, and visit places linked to the start of the Revolution. Or they might be touring colleges, or attending events, at schools like MIT, Harvard, and Northeastern.

The Innovation Trail focuses primarily on what happened after America became an independent nation, and after some of Boston’s early schools like Boston Latin (founded in 1635) and Harvard (founded in 1636) were established. Independence and access to education began to build a foundation for innovation—as did societal changes like the abolition of slavery, women’s suffrage, waves of immigration, and marriage equality—allowing a diverse group of people to collaborate on research and company formation. Add in a desire to make the world better, and money from investors, universities, and government agencies to set up labs and run experiments—and voila, you get a thriving innovation ecosystem that has helped shape the modern world.

Who it’s for.

Visitors, residents, students, and teachers who want to understand more about Boston’s legacy of world-changing innovation.

What’s next.

We’re working on a slate of events, tours, and education-related initiatives for 2024… raising money… and continuing to build awareness of the Trail. We’d love to get you onboard as a supporter of this important new experience in Boston! You can also follow us on social, or get in touch!

Tours & News

Trail Map

Map

Trail Sites

-

Patent Pioneer30 School Street, Boston

If you have an idea for something new, one of the ways to protect it from copycats—and eventually make money from it—is by filing a patent. In the 1860s, this building was the office of a patent law firm that employed Lewis Latimer. Latimer was the son of parents who escaped from slavery in Virgina and fled to Massachusetts.

Audio Guide for This Stop:

-

(In a trial held after his father, George, was re-captured, George Latimer was represented by Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison, the famed abolitionists.) Lewis Latimer had little access to formal education, but after serving several years on a Union gunship during the Civil War—he joined at age 15—he got hired by the patent firm here at a salary of $3 per week, and taught himself how to draft intricate and detailed mechanical drawings. He rose to become head draftsman at the firm. Latimer helped the inventor of the telephone, Alexander Graham Bell, create the drawings used for the telephone’s first patent filing, and later, he worked with other inventors, including Hiram Maxim and Thomas Edison, to extend the useful life of the light bulb from minutes to hours and make it easier to manufacture, filing several patents of his own. By the end of Latimer’s career, he was a member of the Edison Pioneers, a small group of people who had worked closely with Edison in the early stages of his career. He was the only Black person in that group.

-

![]()

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons (left) Alexander Graham Bell, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons (right) -

On your way to the next stop, see if you can spot a statue of Ben Franklin, the prolific inventor and signer of the Declaration of Independence. He attended Boston Latin School, originally located on this site, but ended his formal schooling at age 10 to work in his father’s soap and candle making shop not far from here. Boston Latin was America’s first public school, founded in 1635, offering free tuition to its students of all classes. It still exists, although in a different location.

-

-

Technicolor MoviesTremont Temple, 88 Tremont Street, Boston

The electric light bulb changed a lot of things about life in America. One industry that it gave birth to was the movies; without bright electric bulbs, you can’t have a movie projector. The three men who founded a company called Technicolor in 1914 had become intrigued by early movies—which were in black and white. They thought they could develop a new movie camera and projection system that could show movies in more realistic color.

Audio Guide for This Stop:

-

Two of the founders had graduated from MIT—then called “The Tech”—so the name of their company is a reference to their alma mater. They set up a film processing lab in a railroad car, hitched it to a train, and sent it to Jacksonville, Florida, to shoot the first Technicolor film, “The Gulf Between.” It was shown for the first time here in 1917, and shortly after in New York—mainly to try to interest movie producers and theater owners in the idea of color movies. As the movie industry gravitated to Los Angeles, Technicolor followed it, leaving Boston behind. While you would have been among the first people to see a color movie if you were here in 1917, it wasn’t until 1939—the year that “Gone with the Wind” and “The Wizard of Oz” were made—that Technicolor convinced the movie industry that color was here to stay.

-

![]()

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons -

On the way to your next stop is the Omni Parker House Hotel, where both Boston Creme Pies and Parker House Rolls were invented.

-

-

-

The Ice KingKing’s Chapel Burying Ground, Tremont Street, Boston

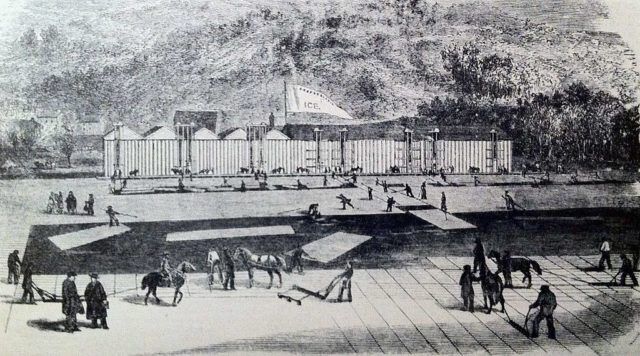

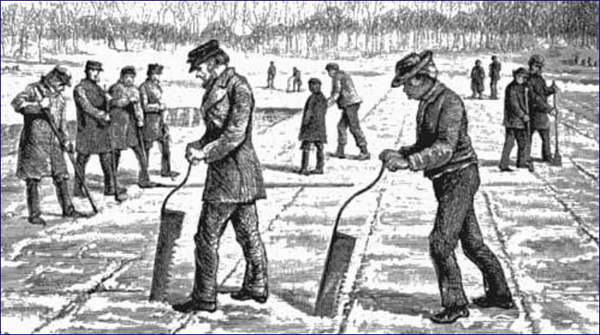

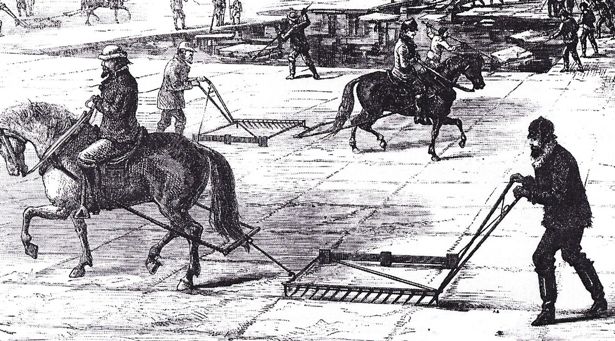

One of the first millionaires in America was a man named Frederick Tudor, who was born in Boston. The business that made him rich? Shipping ice from frozen ponds in Massachusetts around the world, in the days before you could just plug in a freezer and start making your own cubes.

Audio Guide for This Stop:

-

Part of Tudor’s genius was in selling a product that was free—frozen pond water—and using another free product—sawdust—to insulate it when he packed it into sailing ships and sent it around the world. (He tested various ways to keep the ice cold in transit and in storage at its ultimate destination.) Tudor’s ice made it to the Caribbean, India, Hong Kong, and England, and he built a network of ice houses around the world to store it. In warm weather countries like Cuba and Martinique, Tudor’s ice was used to make ice cream for the first time.

-

He would tell his salesmen to give bartenders a free one-year’s supply, after teaching them to make cocktails that benefitted from having ice in them. That created loyal customers. (Year-round access to ice was also helpful to doctors, who used it to treat patients who were suffering from severe fevers.) Along the way, Tudor went bankrupt and served time in debtor’s prison. But he eventually succeeded and became known as “The Ice King.” He died in 1864 in his home on Beacon Hill, and is buried in the back right corner of this cemetery. Look for a small, faded tombstone that says John Tudor, and an explanatory sign nearby.

-

-

-

Combating an EpidemicOutside the Government Center T Stop

One of the most important people in Boston’s early scientific history was an enslaved man named Onesimus, who was “given” to the preacher Cotton Mather by Mather’s congregation, and lived in Mather’s house in the North End. If you look for the white steeple of Old North Church, that neighborhood is the North End, where Onesimus lived.

Audio Guide for This Stop:

-

There’s not much trace of him—or Cotton Mather’s house, which was located near Hanover Street, the neighborhood’s main street. Onesmus was born in the late 1600s, and lived in Mather’s household in the early 1700s. One of the most feared diseases of the time was smallpox, which killed about 30 percent of the people who got it, and left many of the survivors with severe scars—pockmarks—on their faces. Onesimus explained to Mather that in Africa, he had been inoculated against smallpox. His arm was cut open, a small amount of material from a person infected with smallpox was inserted into the wound.

-

-

Though Mather tried to promote the idea of inoculation as a smallpox epidemic gripped Boston in 1721, people at the time were skeptical of a medical procedure that seemed to be based on African customs. (At one point, someone hostile to the idea threw a small bomb through Mather’s window—which luckily failed to explode.) But Mather and a doctor who lived near present-day Government Center, Zabdiel Boylston, gathered data about the survival rates of those Bostonians who were inoculated. In the 1721 smallpox outbreak, only two percent of inoculated people died, compared to almost 15 percent of those who had not been inoculated. This was one of the earliest clinical trials on record in the US, using experimental and control groups to illustrate the effectiveness of inoculation. It would not have been possible without Onesimus.

-

-

Inventing the TelephoneOutside the JFK Federal Building, Cambridge Street, Boston

(Look for a waist-high pedestal with a plaque on it.) Oops. Boston is usually great at preserving important historic buildings, but the one that used to stand right near here, Charles William, Jr.’s shop, was knocked down as part of the “urban renewal” program that got rid of tenement buildings and made space for Boston’s city hall (behind you) and the JFK Federal Building.

Audio Guide for This Stop:

-

After the telegraph had been developed in the 1830s and begun to be used as the first real-time, long-distance communications technology, inventors began thinking about how to improve it. Maybe you could send multiple signals down the same wire, or perhaps even a human voice? The telegraph shop run by Charles Williams, Jr. was a magnet for telegraph tinkerers—including a young telegraph operator who worked for Western Union named Thomas Edison, who hung out after work in this shop.

-

![]()

-

Edison’s first patented invention, an automatic vote-recording machine for Congress and other legislative bodies to use when taking votes, was a flop, but it taught him an important lesson. Elected officials didn’t want to make vote counting faster, because then there was less time to convince their fellow legislators to change their votes. After that, Edison resolved that he would only invent things that people wanted.

But a Boston University professor named Alexander Graham Bell invented something pretty successful here: the telephone. Williams liked the invention, and had the first two telephones installed in his shop and his home in Somerville three miles away (which is still standing, at 1 Arlington Street, Somerville.) His phone numbers? 1 and 2. In the first few years after the telephone’s invention, every piece of telephone equipment was made in this building—until demand got too great.

Why did Bell, who was born in Scotland, went to college in London, and lived much of his life in Canada, invent the telephone here? He was able to establish a network of skilled technicians, and find an early investor who was the father of one of his students at the then-new Boston University. He had people like Lewis Latimer to help him file patents. Innovations don’t happen without money, networks of people to work with you, and a city that has early adopters like Charles Williams Jr.

-

-

Surgery Without Pain (Mass General)55 Fruit St Boston

You can stand on the lawn outside the Bulfinch Building at Massachusetts General Hospital—or, if the hospital is allowing visitors, you can go inside and seek out the Ether Dome. It’s worth seeing from the inside, and it is open to the public as long as there is not a lecture or meeting taking place.

Audio Guide for This Stop:

-

The Dome is a top-floor operating theater that was designed to allow doctors and medical students observe surgeries as they happened, and in the years before Edison’s electric light bulb, it relied on the sun and skylights in the roof to provide enough illumination so the surgeons could see what they were doing. In 1845, the head surgeon at Mass General, John Collins Warren, performed a tooth extraction on a medical student using the gas nitrous oxide to knock out the patient. Unfortunately, the dose wasn’t right, and the patient experienced just as much pain as if the gas hadn’t been used.

-

360 Degree Video inside the Ether Dome -

Warren tried again in 1846, using a different gas, sulfuric ether, and a different person administering it, the Boston dentist William T.G. Morton. This time, after a patient had a tumor from his neck removed, he described the feeling as having his neck scratched a bit. The use of inhaled ether as an anesthetic spread around the world; it allowed surgeons to perform a much wider range of operations without causing pain. Warren was a big deal: he was a founder not only of Mass General Hospital, but also the New England Journal of Medicine, and he served as the first dean of Harvard Medical School. (Warren also is tied to the American Revolution: his father, also a doctor, treated wounded soldiers in the early battles, and his uncle, Joseph Warren, was a leading Patriot who fought and died at the Battle of Bunker Hill in 1775.)

Mass General has been the site of many other firsts, including the first surgery to reattach a limb, in 1962, and the first use of “telemedicine” in 1968 to enable doctors to evaluate and treat patients in another location.

-

-

![]()

Courtesy of the Paul S. Russell, MD Museum of Medical History & Innovation at Massachusetts General Hospital

-

-

Museum of Medical History and Innovation2 North Grove Street, Boston

Showcasing the evolution of medicine, including some of the instruments used in the first surgery with anesthesia, the Paul Russell Museum of Medical History and Innovation opened on the Mass General Hospital campus in 2012. (Free to the public. Currently open Tuesday through Friday, 10 AM to 2 PM, and Saturdays, 11 am to 4 pm from April through October.)

Audio Guide for This Stop:

-

Museum of Science1 Museum Of Science Driveway, Boston

(optional detour) Visit the Museum of Science, founded in 1830 as the Boston Society of Natural History. One of the first museums to bring all of the sciences together in one place. Notable exhibit: Navigating a World with AI, featuring robots from iRobot and Boston Dynamics, and AI-powered artwork by Boston’s Masary Studios. Adds about 20-30 minutes of beautiful walking along the Charles River.

Audio Guide for This Stop:

-

-

Startup Hub (CIC)One Broadway and 101 Main Street, Cambridge

The dot-com era of the late 1990s inspired Tim Rowe, a graduate of MIT’s business school, to start Cambridge Incubator, a company that would start companies. That idea didn’t pan out, especially as the stock market crashed in 2000 and Internet startups with big ideas but very little revenue fell out of favor. But Rowe took the office space he’d rented and started carving it up into small blocks that he could rent to other startups—while also providing services like Internet access, space for events, and free coffee and snacks.

Audio Guide for This Stop:

-

Entrepreneurs helping one another by offering feedback, or connections to potential customers or investors, was a key part of the formula. What started as Cambridge Incubator became Cambridge Innovation Center, and later CIC. Today, the CIC buildings in Kendall may be home to more startups and venture capital firms than any other buildings on the planet. The CIC served as the first Massachusetts address for tech giants like Google, Apple, and Amazon. It was the original address for successful companies like HubSpot, a marketing software company that is now publicly-traded and has an office of its own. CIC now has a global footprint, operating over 1 million square feet of office and lab space in cities like Philadelphia, Rotterdam, Warsaw, and Tokyo. CIC Health, launched during the COVID-19 pandemic, provided testing services to schools, and operated large-scale vaccination clinics at Fenway Park and Gillette Stadium.

-

-

Venture Café, another CIC founded entity, hosts public networking events, panel discussions, and pitch nights. Stop by almost any Thursday night of the year to see for yourself.

Just across Broadway from the tower at One Broadway, you'll see a plaza with a globe fountain in the center. Seek out the "Looking Glass" sculpture, designed by teen creatives from the nonprofit Innovators for Purpose. It's a wonderful photo spot that declares Kendall Square is the "most innovative square mile on the planet."

-

![]()

-

-

Entrepreneur’s Walk of FameOutside the Kendall Square Marriott, Cambridge, near the MBTA station entrance

Created in 2011, the Entrepreneur Walk of Fame recognizes founders and inventors like Thomas Edison, Steve Jobs of Apple, and Mitch Kapor of Lotus Development Corp.

Audio Guide for This Stop:

-

-

MIT Museum314 Main Street, Cambridge

New location of the MIT Museum, reopened October 2022. Showcases ongoing research and ingenuity at the world-famous Institute, while also displaying past achievements through its vast collection— including archives from Polaroid Corp., the pioneering maker of instant cameras, founded a few blocks away. The museum offers a range of exhibitions and installations, a state-of-the-art maker space where visitors can tinker and discover, and ongoing programs.

Audio Guide for This Stop:

-

-

Googling Cambridge355 Main Street, Google Cambridge

If you own a phone that uses the Android operating system, that’s the primary reason that Google now has a sprawling office in Cambridge that employs about 2,000 people (as of 2021.) Way back in the days before the iPhone—2005—Google bought a startup whose two co-founders were based in Cambridge and Silicon Valley. That startup was called Android, and it was working on new operating system software for mobile phones. Its Cambridge-based co-founder, Rich Miner, began to hire engineers to work alongside him after the acquisition.

Audio Guide for This Stop:

-

So Boston not only brought the world the telephone in the 19th century, but it also helped to create the world’s most popular smartphone operating system of the 21st century, with more than 2.5 billion Android users. As of 2021, Google’s Cambridge employees were working on projects for youtube, Google Travel, and Google News.

-

![]()

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons -

Secret spot: While you can’t go into Google to enjoy their free cafeteria food, snacks, and coffee, you can go up to the Kendall Rooftop Garden, which looks in on some of the Google space. It is being renovated but will open in Summer 2022. It’s a great place for a rest or a picnic lunch.

-

-

-

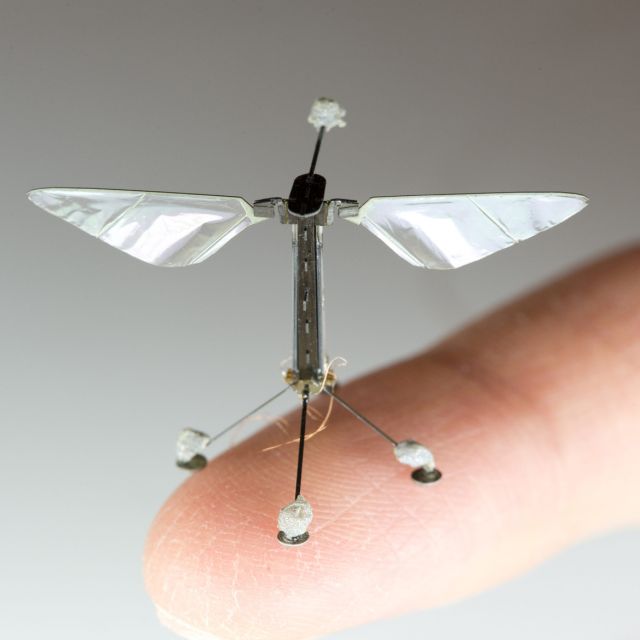

MIT’s Cutting Edge (Stata Center)32 Vassar St Cambridge

MIT’s motto is “mens et manus,” Latin for “mind and hand,” and that blend of intellectual exploration and practicality is part of what has made the school so successful at producing not just new breakthroughs, but also entrepreneurs, startups, and major, publicly-traded companies. Inside the Stata Center at MIT are labs focused on computer science, artificial intelligence, and robotics (they gave birth to iRobot Corp., maker of the Roomba robotic vacuum cleaner), and a small, ground-floor exhibit about student “hacks,” or pranks, through the years.

Audio Guide for This Stop:

-

The creator of the World Wide Web, Tim Berners-Lee, works here—though the web was invented when Berners-Lee worked in Switzerland. The current building was designed by the California architect Frank Gehry, and named for Ray Stata, an MIT alumnus who co-founded the chip company Analog Devices. Bill Gates, the Harvard drop-out who co-founded Microsoft, was also a major donor.

-

-

This site was previously home to the Rad Lab, which was set up in the years leading up to World War II to develop key radar technologies. Many historians regard these technologies as crucial to the Allied victory over Hitler, helping the Allies to “see” enemy ships, planes, and other targets at long distances, and better direct their guns and bombs. It was also in this building that the term “hacker” was first used—in a positive context—and many of the origins of hacker culture had their roots, as part of the MIT Model Railroad Club. (Closed to the public during COVID pandemic.)

-

-

-

Broad Discovery Center415 Main St, Cambridge

The Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard seeks to better understand the roots of disease and narrow the gap between new biological insights and creating impact for patients. (Pronounce “Broad” to rhyme with “road” and people will think you work there.) Beginning in the 2010s, the Broad has made key contributions to “genome editing” and a technique known as CRISPR (pronounced “crisper”), which is helping to improve our knowledge of how diseases work, and develop new types of therapies. Launched in October 2022, the new Broad Discovery Center is an active, public educational space that showcases how researchers in Kendall Square and around the world are seeking to understand and treat human disease.

Audio Guide for This Stop:

-

The Broad Discovery Center has five galleries where visitors can immerse themselves in interactive and informative exhibits. Visitors learn how researchers at Broad and its partner institutions are teaming up with collaborators across the globe to chase down the roots of psychiatric conditions, cancer, infectious diseases, and more, develop new strategies for treatment, and build datasets and technologies to share with other scientists.

Optional stop: Directly across the street is the Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research (500 Main Street), which has public galleries that are accessible on weekdays. These feature scientific photography and art, and provide an overview of current cancer research at MIT.

-

-

-

Human Genome Project (Whitehead Institute)455 Main St, Cambridge

The Whitehead Institute was created in 1982 by philanthropist Jack Whitehead and David Baltimore, an MIT professor and Nobel Prize winner. A key part of the vision was assembling a supergroup of the world’s top biomedical researchers in one building, and eliminating “virtually any impediment to their pursuit of scientific discovery,” supplying ample funding and the most sophisticated lab equipment, but limited bureaucracy. (It’s an independent nonprofit affiliated with MIT.)

Audio Guide for This Stop:

-

When the Human Genome Project was seeking to map the entire human genome—described as the world’s largest collaborative biological project—the Whitehead was the single largest contributor. The Whitehead’s Center for Genomic Research was spun out in the early 2000s to create the neighboring Broad Institute. Groups at the Whitehead are currently seeking to understand the biology of infectious diseases; why cancer cells behave differently from healthy cells, and what enables them to multiply so quickly; new ways to model and understand how the brain works; and many other biological domains.

-

-

![]()

-

-

Biotech Trailblazer (Biogen)115 Broadway, Cambridge

To get over to Broadway, take the walkway next to the Broad Discovery Center and head toward Danny Lewin park, or take Ames Street. Biogen was one of the earliest biotech companies. Two of its founders, Walter Gilbert and Phillip Sharp, were professors at Harvard and MIT respectively; both were awarded Nobel Prizes.

Audio Guide for This Stop:

-

Biogen’s mastery of recombinant DNA technology—using enzymes to “cut and paste” sequences of DNA to achieve therapeutic effects—enabled it to develop a vaccine for hepatitis B, as well as the drug Avonex, which is used to treat multiple sclerosis. (The name Biogen originally referred to “Biotechnology Geneva,” the city where the company was founded in 1978.) Biogen went public in 1983, and first set up a manufacturing plant in Cambridge in 1986. A Biogen drug approved in 2021, Aduhelm, targets Alzheimer’s disease.

-

![]()

-

-

Internet Accelerator (Akamai)145 Broadway, Cambridge

Across the plaza is the campus of the headquarters of Akamai, a company that began life at MIT. Its original idea was to set up a network of servers around the world to cache, or store, content closer to where people wanted to access it—making everything show up faster on web browsers. Some of the company’s first successful large-scale demonstrations, in 1999, involved the delivery of a movie trailer for “Star Wars: The Phantom Menace” and ESPN’s March Madness college basketball coverage.

Audio Guide for This Stop:

-

(Danny Lewin, a co-founder of the company, was aboard a plane that left Boston on the morning of September 11th, 2001, and was killed trying to disrupt the hijacking.) Akamai today operates more than 300,000 servers around the world, and generates $3.5 billion in annual revenue—but when the founders were still at MIT, they were famously finalists in the school’s annual business competition, but not a winner.

-

![]()

-

-

-

Getting to the Moon (Draper Labs)555 Technology Square

Walk down Broadway and take a left at Technology Square. At 555 is Draper Labs, where you’ll see a giant moon hanging in the lobby. (There are sometimes displays open to the public as well.) Draper began life as a lab inside MIT; eventually it was spun out to be an independent research and development lab. Among its greatest achievements are the guidance computers that enabled Apollo spacecraft to successfully travel to and land on the moon. One of the software developers who wrote the code that ran these guidance computers was Margaret Hamilton, who later founded two companies and is credited as one of the people who defined the field of “software engineering.”

Audio Guide for This Stop:

-

Short video on Margaret Hamilton -

Short video on how the Waltham Watch Company helped Draper engineers

-

-

Vaccine Breakthroughs (Moderna)200 Technology Square, Cambridge

A few steps down from Draper Labs is the headquarters of Moderna Pharmaceuticals, which was founded in 2010 to explore the potential of modified RNA molecules (hence the name “mod-RNA”) to treat diseases or serve as a vaccine. The company’s founders were a team of university professors and venture capitalists who were born in Canada, Lebanon, and the United States, and the company’s first CEO was born in France.

Audio Guide for This Stop:

-

In 2020, Moderna developed and received emergency use authorization for a COVID-19 vaccine based on its modified RNA technology. Moderna’s vaccine was among the fastest vaccines ever developed.

-

![]()

-

-

-

Instant Photos (LabCentral)700 Main Street, Cambridge

It’s hard to find a building with more ties to more different eras of innovation than this one. When first constructed, it was the Davenport Car Works, one of the country’s first manufacturers of passenger railroad cars. (Davenport pioneered the use of a center aisle for easy movement and greater passenger capacity, as well as the reversible seat, which could be switched to face forward if the train changed directions.)

Audio Guide for This Stop:

-

Later, it was home to the Walworth Manufacturing Company, where a Walworth employee invented an adjustable wrench with incredible gripping power called the Stillson that is still in use today. In 1876, when Walworth was based here, this building was the site of the first “long distance” demonstration of Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone, from a Walworth office in Boston to this building, with Thomas Watson manning the equipment on this end. The goal was to prove the usefulness of the telephone in business.

-

Land and instant photography -

In the late 1930s, an inventor named Edwin Land moved in. On a vacation in New Mexico, Land’s daughter wondered why the photos taken in traditional film cameras couldn’t be seen right away—they had to be developed in a lab. That innocent question led Land to invent the first instant camera, and start a company called Polaroid to market it. Even though Polaroid’s headquarters moved elsewhere in Cambridge, Land kept his private research lab here. One entrepreneur who was inspired by Land was Steve Jobs, the co-founder of Apple Computer, who said that Land “saw the intersection of art and science and business, and built an organization to reflect that.”

Today, this brick building is occupied by LabCentral, a shared laboratory space used by dozens of fledgling biotech companies. When the building is open, you can go into the lobby and see small displays about the telephone and instant photography. If it's not open, see if you can find the accents above the building's windows that include fragments of railroad ties — a nod to the site's past.

-

-

The Last Candy Factory810 Main St Cambridge

This building from 1927 is a link to an era when Cambridge was one of the country’s manufacturing centers. Throughout much of the 1800s and well into the 1900s, the city was home to companies that made bicycle tires, fire hoses, telescope lenses, soap, pianos, ping-pong paddles, and ice cream.

Audio Guide for This Stop:

-

There were also at one point 66 different candy companies in Cambridge, making everything from candy hearts for Valentine’s day to Squirrel Nut Zippers to lemon drops. (The Fig Newton cookie was also invented in Cambridge, in 1891—even though they were named for the nearby city of Newton.) This building is the last operating candy factory in Cambridge, owned by Tootsie Brands. The company unfortunately doesn’t offer tours, in part because candy companies are notoriously secretive about the equipment and processes they use to make candy—“Charlie and the Chocolate Factory” wasn’t too far off base. Inside, they make 26 million pieces of candy a day. Why is that number so high? The factory is the only place in the world that Sugar Babies and Junior Mints are made—both of which are small little morsels.

-

-

-

If you look through the parking lot on the right side of this building (or walk over to 250 Massachusetts Avenue), you can see the top of another candy factory. That one, the former New England Confectionery Company, or NECCO, has a water tower on top that now sports a DNA helix. When the building made NECCO wafers and conversation hearts (“Be Mine”)—from the 1920s until 2003— the water tower was painted like a rainbow roll of that chalky candy. At one time, it was the world’s biggest candy factory under one roof. The building is now occupied by the Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research, the main research lab for the Swiss biopharma company. (Fun fact: like Willie Wonka’s factory, the building has glass elevators.) While Novartis and other biopharma companies design and test new drugs here in Cambridge, for the most part when they create something that is approved by the FDA and can be prescribed to patients, it’s made elsewhere. Cambridge’s real estate has become too valuable to do manufacturing these days—though the Cambridge Brands factory is hanging in there.

Across Main Street there is a mural that tells the story of candy manufacturing in Cambridge.

What next? There are other “off Trail” sites you can visit in Cambridge and beyond. (Scroll down to "Beyond the Trail.") If you’re hungry or thirsty, drop by Toscanini’s Ice Cream or Miracle of Science, two favorite hangouts of the Kendall Square and MIT communities a few steps away from the Cambridge Brands factory.

-

FAQs

Where do I start the Innovation Trail?

You can start the Innovation Trail in Downtown Crossing, near the Irish Famine Memorial and the Old South Meeting House, or in Cambridge near Central Square. To get to the Boston start, you want to get off on the MBTA’s Park Street, Downtown Crossing, Government Center, or State Street stops in Boston. All are less than a five minute walk to the Stop #1. To get to the Cambridge start, get off at the MBTA’s Red Line stop at Central Square in Cambridge. Walk down Massachusetts Avenue toward 810 Main Street.

If you scroll to the top of this site, you’ll see buttons that will rearrange the map depending on whether you want to start in Boston or Cambridge.

Another option is to start at the Museum of Science, and walk either toward the Boston or Cambridge side of the Trail. To do that, you can use the MBTA’s Science Park stop on the Green Line. The Kendall Square stop on the Red Line is helpful if you want to only walk the Cambridge side of the Trail.

Where are the restrooms?

The Boston Common Visitors Center, near the start of the Innovation Trail, has public restrooms. You may also be able to use restrooms inside the Omni Parker House Hotel or Boston’s Old City Hall (between Stops #1 and #2), Flour Bakery or Starbucks (on Cambridge Street between Stops #5 and #6), the Wyndham Boston Beacon Hill (between Stops #5 and #6), the Liberty Hotel (between Stops #7 and #8), One Broadway (Stop #9, in the restaurant Shy Bird or Brothers Marketplace), the Boston Marriott Cambridge (at Stop #10), A4 Café (between Stops #19 and 20), or Toscanini’s Ice Cream (after Stop #21.) All these stop numbers assume you are walking the Trail from Boston to Cambridge.

How long does it take to walk the Trail?

That depends on how many of the museums you go into, but if you’re using this site’s self-guided tour and you opt not to visit any of the museums, you can walk the full Trail in about three hours.

What if I don't have the time to walk the full Trail?

You could walk just the Boston half, or just walk the Cambridge half. (Click the button that says “Start from Cambridge” to see the stops listed starting from near Central Square.) You could also visit one of the great museums on the Trail, and perhaps add a nearby site before or after.

What do I get when I buy a ticket on one of the public tours?

Our ticketed tours for the public currently run Thursday, Friday, Saturday, and Sunday between May and October and are facilitated by the award-winning Cambridge Historical Tours. They are 90-minute walking tours of the Cambridge portion of the Trail. They start and end in Kendall Square, starting at the Boston Marriott Cambridge hotel and ending outside of the MIT Stata Center (just a 5 minute walk back to the starting point). They do not include stairs, and so are very accessible to people using strollers or wheelchairs. These tours have ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ ratings and glowing reviews on TripAdvisor and Google.

Do we go into museums on the ticketed tours? What about on self-guided tours?

The ticketed walking tours, led by Cambridge Historical Tours, cover just the Cambridge side of the Trail. The ticket price does not include admission to the MIT Musuem or other museums, but they do go into galleries at the Broad Institute/Broad Discovery Center, and MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Lab when the buildings are open. We encourage you to check out the museums on the Trail before or after your guided walking tour. The Broad Discovery Center and MGH Museum of Medical History & Innovation offer free admission; the MIT Museum and Musuem of Science have admission fees.

If you are walking the Innovation Trail as a self-guided our, we encourage you to check out the museums that are of greatest interest to you. All of them have restroom facilities; the MIT Museum and Museum of Science also have gift shops. Only the Museum of Science has a cafeteria and beverages available for sale.

If I'm driving into Boston, where can I park?

The Pi Alley Parking Garage at 275 Franklin Street is closest to the start of the Trail in Boston. The Boston Common Garage and Center Plaza Garage are both a short walk from the start. If you park near the Boston start and walk all the way to Cambridge, it’s easy to take the MBTA back from the Central Square stop on the Red Line to the Park Street Stop on the Red Line. (This ride is three stops.)

If you’re starting on the Cambridge end, the 55 Franklin Street garage in Cambridge is well-located. If you walk all the way to Boston, you can take the MBTA’s Red Line from Park Street to Central Square to return to your car. (This ride is three stops.)

Can I experience The Innovation Trail on my own bike, or a Bluebike?

Absolutely. If you’re using Bluebikes, Boston’s bike-sharing program, there are stations at the Boston and Cambridge end of the Trail, and there are also places to drop bikes near all four of the museums on the Trail, if you’d like to go inside the Museum of Science, MIT Museum, Broad Discovery Center, or Museum of Medical History & Innovation at MassGeneral.

How do I arrange for a custom guided tour?

See the “Tours & Events” section of this site for upcoming tours and activities open to the public. If you’d like to arrange for a private group tour of the Trail, these can be arranged with our partner, Cambridge Historical Tours. Send us a note with your requested dates and we’ll respond ASAP.

Why isn't ______ on The Innovation Trail?

We’d love to hear from you about what you think should be included. Either tag us on social media (@bostoninnotrail), or click the menu at the upper right corner of the page and choose “Connect with Us” to send us your thoughts.

Many innovative people and places aren’t included simply for reasons of geography; we wanted to create a walkable route in Boston and Cambridge, close to hotels, T stops, and other tourist destinations. Some aren’t included because there just isn’t a building/plaque/marker/historic home/museum or anything to see. In other cases, we had to be selective: how much (and what) do you highlight at a university like MIT or Harvard, for instance? But see the “Beyond the Trail” section of the site for interesting sites located around Greater Boston, some a short distance from the Trail itself. And we plan to continue evolving and adding to what’s here with input from you.

How might the Trail better reflect Boston’s diversity?

In creating the Trail, we wrestled with the city’s history, where many people involved in forming institutions, being educated by those institutions, and creating new inventions were white men. Boston, like many other cities across the country, has not exactly been a place of equal opportunity over the course of its history, and that reality is reflected in our legacy of innovation.

One of the Trail’s aims is to work with historians and others in the community to identify stories and contributions from BIPOC, women, and members of the LGBTQ+ community whose work may have not yet been properly recognized and celebrated. We will endeavor to highlight the work being done by other organizations on this issue (See “Beyond the Trail,” under “Societal innovations and social change” for links.) We will also highlight work being done by existing sites on the Trail, like MassGeneral, to detail the diverse innovators who have contributed to their success and progress. If you’d like to participate or contribute, please click “Connect with Us” and send us an email. We plan to share additional stories on this website, on our social feeds, and in live tours.

Is the Innovation Trail dog‑friendly?

Yes. We have had many dogs learn about innovation along with their human followers. One caveat: dogs are not permitted into any of the museums, offices, or MIT buildings on the Trail, unless they are service animals.

If you are walking the Trail with a dog, please tell them that the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard was the first to sequence the complete dog genome (a boxer named Tasha.) More info here.

Beyond the Trail

Any time you try to curate a walkable set of sites, you’re forced to leave some things off—no matter how amazing—because they may require a few extra footsteps, a drive, or a trip on the T. But this group of museums, national park sites, monuments, and other university buildings are each well worth a visit. Many of them provide important context about the social, educational, and historical foundations that made possible the innovation ecosystem that exists in Boston today. We’ve listed them in order of their proximity to the Innovation Trail.

MIT Media Lab

The Media Lab at MIT has spawned products like Lego’s Mindstorms robotics kit, the iWalk prosthetic foot, and the video game “Rock Band.” A first-floor exhibition space, showcasing the work of professors and students, is open to the public.

Henri A. Termeer Square

Henri Termeer, born in the Netherlands, was one of the pioneering executives of the early biotech industry, serving as CEO of Genzyme for nearly three decades. At the company, he helped shepherd science out of the lab and into the marketplace, delivering treatments for patients with rare (and often fatal) diseases like Gaucher and Fabry. Termeer helped elevate the profile of the biotech industry in Massachusetts and nationally. Genzyme was ultimately acquired for $20 billion by the French pharmaceutical company Sanofi. Termeer died in 2017. The square includes a statue of Termeer, quotes, and a reflecting pool inspired by the book “The Giving Tree.” The building at 500 Kendall Street, on the south side of the square, was originally built as Genzyme’s headquarters. It was the first LEED platinum-certified green building of its size in the US.

The Ether Monument

Look for the Ether Monument in the northwest corner of the Public Garden, near the intersection of Arlington and Marlborough Streets. It commemorates the first use of anesthesia; since several people claimed to have “discovered” ether for medical applications, the monument depicts a medieval doctor in Moorish robes, representing a generic Good Samaritan, anesthetizing a patient. An inscription says, “To commemorate that the inhaling of ether causes insensibility to pain.”

Park Street

First subway system in Western Hemisphere (1897), built to relieve traffic congestion in downtown Boston. To power the subway, the Thompson-Houston Company had to build one of the most powerful electric plants in the world, in 1895. New York City and Boston were in a fierce competition to build the first subway over more than a decade; Boston was victorious. There are some historic displays at Park Street, and older trolleys at Boylston Street, the first two stations built.

The Father of Venture Capital

The former home of Harvard Business School professor Georges Doriot. A French immigrant Doriot started what is regarded as the first venture capital firm (1946), Boston-based American Research and Development. Venture capital firms provide funding to entrepreneurs based on the merits of their idea; that money is a crucial driver of innovation in many fields. Among Doriot’s investments: Digital Equipment Corp., which turned the firm’s $70,000 investment into more than $350 million. At one point, Digital was the second largest technology firm in the world, after IBM. (Private home, not open to the public.)

Programming Pioneer

Inside Harvard’s new Science and Engineering Complex, you can find a portion of the Harvard Mark 1 Computer, and a display featuring programming pioneer Grace Hopper and the very first computer bug (an actual moth trapped in the relays.) The computer was built during World War II, and some of the first programs run on it were simulations related to the design of the first atomic bomb.

Massachusetts Innovations video wall

“Massachusetts Innovations — Transforming the World.” Detailed display and video wall featuring fifty of the “greatest hits” of Massachusetts innovations. In Terminal C, near Gate C9. (This display is inside airport security, so you’ll need to be flying in or out of Logan Airport to see it.)

Harvard Tours

Students run these free tours of Harvard Yard, touching on the university’s history and the student experience. Many other operators run ticketed tours of Harvard.

Ellen Swallow Richards House

Home of the first woman to graduate from MIT, and the university’s first female instructor. Ellen Swallow Richards was the founder of the home economics movement, which sought to apply science in the home. She used this house as a laboratory, continually updating its ventilation, plumbing, and heating to create an optimal, safe, and efficient living environment. Swallow Richards also did pioneering work in water safety testing, and creating school lunch programs for low-income children. (Private home, not open to the public.)

Harvard's Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments

Harvard University has been acquiring scientific instruments since 1672 — including magnificent orreries, compasses designed by Galileo, electrical apparatus donated by Benjamin Franklin, and cyclotron control panels. The Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments is now among the largest university collections of its kind in the world. Admission is free. See website for current hours. The collection is located inside the Harvard Science Center, a short walk from Harvard Square.

Charles River Museum of Industry & Innovation

The Boston Manufacturing Company (1814), located here, was the first fully-integrated, water-powered cotton textile mill in the world—raw cotton entered at one end and came out as finished cloth at the other. It was also the first modern industrial corporation, pioneering the business model for organizing a manufacturing concern that remains the global standard today. The site now houses the Charles River Museum of Industry & Innovation, dedicated to telling the story of technology as a human endeavor that produces a variety of outcomes. Exhibits explore Waltham’s role in the rise of American industry, from textile manufacturing to machine tools, power systems, timekeeping (the Waltham Watch Company), and transportation (Metz motorcars and Orient bicycles).

Paul Revere & Son Copper Rolling Mill

In 1801 Paul Revere began rolling copper for the U.S. Government. The 9 acre Paul Revere & Son Heritage Site is a park and buildings that contain displays about the first copper rolling mill in America—as well as temporary exhibits focussing on innovation and history. (One focuses on Reebok, the sneaker company that was once headquartered in Canton.) A larger Paul Revere Museum of Discovery & Innovation is in the planning stages.

Lowell National Historic Park

Learn about the history of the Industrial Revolution by visiting mill buildings, seeing equipment operate, riding historic trolleys, and visiting the boardinghouses where mill workers lived.

Samuel Slater Experience

Opened in 2022. Features more than twenty immersive exhibits that make the history of the American Industrial Revolution come alive with projections and full-scale recreations. Raised in the UK, Samuel Slater was known as “Slater the Traitor” for bringing British textile-manufacturing technology to America. The museum features a recreation of Slater’s office, mill worker housing, a working water wheel, and an interactive textile design station.

Connect with us

Connect with us

Share your feedback….join our email list to stay updated…or send us your request for a private group tour.

If you’re requesting a private tour, please share with us the number in your group, the date (or dates) and time(s) you’re interested in, and if you have a preference on the timing and length of the tour.

To keep up with what’s new (and old) on the Innovation Trail, follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, LinkedIn, or YouTube!

Charter Catalysts

-

Sarah Alger

-

Daniel Berger-Jones

-

Janice Bourque

-

Kristen Collins

Communications Strategy Consultant; Author, “The Front Steps Project”

-

George Comeau

-

Damon Cox

-

Greg DeFrancis

-

Michael Dornbrook

-

Jazz Dottin

-

Steve Grossman

Initiative for a Competitive Inner City; former Treasurer of Massachusetts

-

Tom Hopcroft

-

Dan Kakabeeke

-

Scott Kirsner

InnoLead / Boston Globe / Author, “Innovation Economy”

-

Gavin Kleespies

-

Robert Krim

Author, “Boston Made”; Founder, Entrepreneur Innovation Center at Framingham State University

-

Cassandra Lee

-

Carrie Nash

-

Dave O’Donnell

-

Maggie O’Toole

-

Tom Paine

-

Abbey Phillips

-

Mike Quinlin

Commonwealth Marketing Office

-

Erika Reinfeld

-

Tim Rowe

-

Namrata Sengupta

-

Philip Swain

-

Marieke van Damme

-

Kate Viens

-

Karen Weintraub

Author, “Born in Cambridge”; USA Today

-

Jane Wilkinson

-

Sam White

Co-Founder, Greentown Labs & Founder, Nano-Ice

-

Thanks to Visual Dialogue for the Innovation Trail creative concept, design, and website

Susan Battista

Luke Hatfield

Will Kastrinakis

Fritz Klaetke

Kristen McNally

Support the Trail

Donate NowThe Innovation Trail is a grassroots initiative—and we need your support. Our goal is to tell the stories of how innovations born in Boston shaped our world, and to inspire future generations of scientists, entrepreneurs, engineers, and educators. We’ve recently launched a schedule of regular public tours, but we have BIG plans to make this a must-do field trip, a more immersive and tech-forward experience, an essential part of any visit to Boston—and yes, eventually even posting signs or painting a line on the sidewalk. (If the Freedom Trail and an MIT fraternity can do it…. why not us?) We aren’t funded by any city agencies or universities. Our financial support comes entirely from people and organizations who believe in innovation as a force for good in the world. Is that you?

You can make a donation using the big red button at right, or by mailing a check to The Innovation Trail of Greater Boston, 217 Hanover Street, PO Box 130386, Boston MA 02113. The Innovation Trail is a 501(c)3 non-profit organization, and your donation is tax deductible as allowed by law.

-

Henry Ancona

-

Peter Bleyleben

-

Michael Dornbrook

-

Eran Egozy

-

Brad Feld

-

Eric Giler

-

Cary Goldberg

-

Marina Hatsopoulos

-

Maia Heymann

-

Tom Hopcroft

-

Geoff Hyatt

-

Scott Kirsner & Amy Traverso

-

Harry Kirsner

-

Bob Krim & Dr. Kathlyne Anderson

-

John Landry

-

George Mabry

-

Michael Mark

-

Robert Mason

-

Tom Paine

-

Alex Rigopulos

-

Namrata Sengupta

-

Reed Sturtevant

-

Phil and Roseanne Swain

-

Chris Weaver

(The Innovation Trail is a 501(c)3 non-profit organization, and your donation is tax deductible as allowed by law.)